1915 SPRING OFFENSIVES

German lines with an “X”.

Artois and Champagne

The end of mobile warfare in 1914 left the Germans in control of most of Belgium and of some of the most important industrial areas of France. The opposing lines stretched from the Channel coast near Nieuport all the way to the Swiss frontier. At the beginning of 1915, the trench system was still fairly rudimentary – sometimes little more than holes in the ground hastily joined together. In some places the terrain was unsuitable for the digging of trenches. In the Vosges mountains they sometimes had to be cut into rock with explosives. At this stage the French provided by far the largest Allied army, although the BEF grew as new formations arrived.

French Winter Offensives and the Strategy of “Nibbling”

French offensives continued over the winter. Joffre’s strategy was one of constant offensives, “nibbling” (as he called it) the enemy. He aimed to pinch out the great bulge in the German line – the Noyon Salient – by attacking in Artois and Champagne. But the First Battle of Artois (27 September–10 October 1914), an ambitious attempt to capture key objectives, including the dominating heights of Vimy Ridge that overlooked the German-held Douai plain, made little headway and was ended in early January. Another offensive was begun in Champagne on 20 December 1914, which continued in stages until the end of March. Again, despite fierce fighting, the French had little to show for this effort except 240,000 casualties.

German Gains: Chemin des Dames and Hartmannsweilerkopf

The Germans captured the high ground of the Chemin des Dames (“Ladies’s Road”, named after Louis XV’s daughters) running east and west in the départment of the Aisne in November 1914, and in January 1915 a German attack seized the last French position on the plateau, Creute farm (later known as the Dragon’s Cave). In the Vosges, a bitter struggle for the Hartmannsweilerkopf peak resulted in 20,000 French losses over four months before they secured the heights in April.

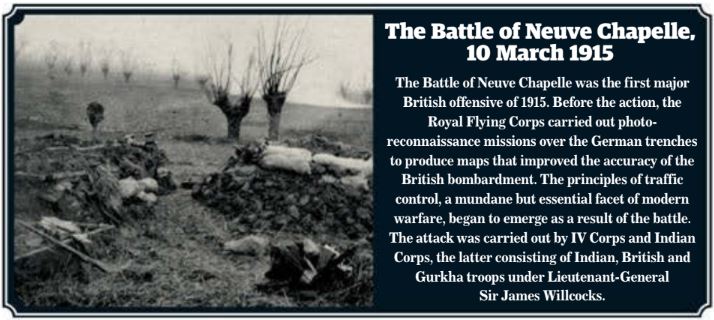

The Importance of Artillery: The Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The early fighting in 1915 demonstrated how important heavy and accurate artillery fire was to battlefield success, particularly now the armies were faced with siege warfare. The British offensive at Neuve Chapelle on 10 March gave further evidence confirming this reality. The battle was well planned by Haig’s First Army staff: the initial bombardment, which was heavy by contemporary standards and lasted only 35 minutes, mostly overwhelmed the German infantry and allowed the British to take the front-line trenches. But resistance on the flanks, the difficulty of following up the initial success and the arrival of German reserves meant the battle soon bogged down. A mere 1,100 m (1,200 yds) was gained for 13,000 British and 12,000 German casualties.

Spring Offensives of 1915: St-Mihiel and the Second Battle of Artois

With the exception of the the German attack at Ypres in April, it was the Allies who remained on the offensive in Spring 1915. French First and Third Armies fought a bloody and unsuccessful battle to reduce the St-Mihiel salient (5–18 April), and Joffre launched another hammer blow in Artois in May. Bad news from the Eastern Front – the Central Powers inflicted a major defeat on the Russians at Gorlice – Tarnow in early May – lent particular urgency to this offensive. It also offered an opportunity to strike in the West while the Germans were heavily committed in the East.

The Second Battle of Artois: Vimy Ridge and Trench Warfare Stalemate

Joffre ordered D’Urbal’s Tenth Army to smash through the German defences in Artois and re-open mobile warfare. On 9 May, Tenth Army, with 1,075 guns (including 293 heavies), attacked Vimy Ridge and positions fl anking it. The main attack in the centre was assigned to Philippe Pétain’s XXXIII Corps.

The defenders wilted under the weight of the bombardment, and within 90 minutes, the 77th and Moroccan Divisions had pressed forward onto the crest of Vimy Ridge. Then, the problems of trench warfare reasserted themselves. Lacking modern radio communications, reserves could not be summoned forward to exploit the gains. When they did arrive, it was too late as German reserves fi rst shored up the front and then drove the attackers back.

The Battle of Aubers Ridge and Festubert: Attrition Warfare Begins

On 9 May the BEF again attacked over the Neuve Chapelle battlefi eld after another brief bombardment. In a day’s fi ghting Haig’s First Army achieved nothing apart from casualties of 11,000 in what became known as the battle of Aubers Ridge. Sir John French was pressed by the French to continue offensive operations, and, after reverting to a bombardment that lasted four days, on 15–16 May, First Army attacked at Festubert with the aim of infl icting heavy casualties on the Germans and pinning their forces to this front.

This brought some modest gains, but again at the price of heavy losses. Festubert was the fi rst time the British fought a deliberately attritional battle, and the limited success helped to create the idea that “artillery conquers, infantry occupies” that was to have terrible repercussions in July 1916.

Originally posted 2025-01-09 15:27:34.