After the death of Pope Francis, the thousand-year-old liturgy of the conclave begins: the most secret rite of the Catholic Church.

The process of electing a pope, the so-called conclave, is a very ancient rite, which has evolved over the millennia (popes have existed for about 2,000 years). A complex procedure rich in curiosities and peculiarities: here’s how it works.

Conclave: yesterday as today?

Originally, the entire community of the faithful chose Peter’s successor. But as soon as the office of pontiff became a coveted political position, the election transformed into a feud between factions of candidates: in 366, dozens of deaths were counted among the supporters of Ursino and those of the future Pope Damasus I.

Starting from 1274, new rules were formalized, until the ceremony took its current form with the election of Pope Gregory XII (1335-1417). The rules of that conclave have remained more or less in force until today (although relaxed in the last century): no contact with the outside world, under penalty of excommunication, community life in a hall, a single dish for both lunch and dinner and, after five days, only bread, water, and a little wine.

Who chooses the pope?

Upon the death of Pope Mark in 336, there had already been an attempt to limit the electors to a restricted group of clergy. “But the current form of the election took shape with Gregory VII in the 11th century; it was he who had the pope chosen only by the cardinals (as still happens today), to exclude the influence of the aristocratic families of Rome, also establishing a two-thirds majority.

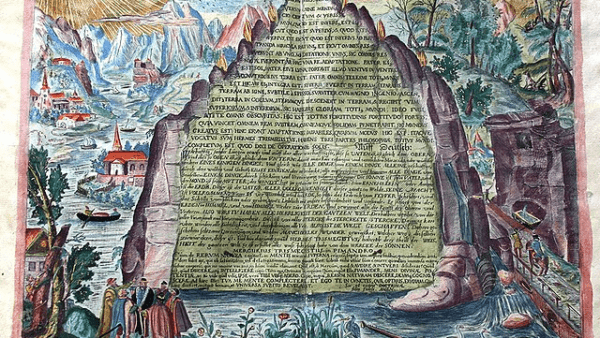

Why is it called a conclave?

The enclosure, however, was imposed on the cardinals gathered in Viterbo (then the papal seat) in 1270, after more than a year of fruitless meetings: the electors were locked cum clave (hence “conclave”) in the episcopal palace, from which the indignant people even removed the roof to pressure them to decide. It took a total of 33 months to elect Gregory X (1210-1276).

Who holds the key? The role of the claviger

This coveted role derives from that of the Marshal of the Holy Roman Church, a figure appointed since the 13th century to close the access doors to the cardinals’ rooms during the conclave. This task still falls to the claviger, who takes responsibility for “sealing” the Sistine Chapel, where the pontifical vote has taken place since 1492.

Behind closed doors

Only in the 19th century was the obligation of secrecy introduced, still applied today to protect the cardinals’ freedom from any political interference. In 1903, for example, the unexpected election of Pius X was due to external pressure: the Austrian crown appealed to a right of veto, later abolished, to block the favored Cardinal Rampolla.

Age and elector limits

Paul VI (elected in 1963) set the age limit for entering the conclave at eighty years old; for the older cardinals, however, there is still the possibility of their opinions carrying weight in the two daily meetings of the full College of Cardinals, which take place during the 15-day waiting period between the pope’s death and the opening of the conclave. Paul VI also set the maximum number of cardinal electors at 120 and facilitated the choice of the new pontiff by admitting a runoff, or a simple majority, after 30 inconclusive ballots.

How is the vote taken today?

The manual for the conclave issued by Pope Wojtyla (1920-2005) is followed “to the letter.” John Paul II established that the election must always take place in the Sistine Chapel (as has been the case since 1878). He also recognized the “ordinary way,” i.e., scrutiny, as the only valid procedure, abolishing two methods still formally in force: the “compromise” (as in Viterbo) and the so-called “inspiration” 1 (i.e., unanimous acclamation “by viva voce” by the cardinals).

Archaic ritual

When the Master of Pontifical Liturgical Celebrations intones “extra omnes” (meaning “everyone out”), nothing more is allowed to leak outside. The ballots are distributed; they are rectangular and foldable in half: the upper half bears the inscription Eligo in Summum Pontificem (I elect as Supreme Pontiff), and the lower half has space to write the chosen name.

Before depositing the ballot in the urn, each cardinal pronounces a solemn oath aloud: “I call to witness Christ the Lord, who will be my judge, that my vote is given to the one whom, according to God, I think ought to be elected.” He then places the ballot on the plate covering the urn and uses the same plate to introduce it into the container. During the counting, the first cardinal scrutineer takes the ballot, opens it, observes the name indicated, and passes it to the second scrutineer who, having also ascertained the name, passes it to the third, who reads it aloud.

As he proclaims the name, the scrutineer pierces the ballot with a needle at the exact point where the word Eligo is located and threads it with the others onto a string: at the end of the scrutiny, the two ends of the string are tied to form a knot. These are archaic procedures aimed at ensuring the most secure preservation of the ballots and preventing tampering.

Black smoke or white smoke?

Once it is ascertained that a pope has not been elected, the rule prescribes that all electoral material be destroyed. Ballots and papers are placed in an old cast-iron stove and burned.

Black smoke comes out of the chimney mounted on the roof of the Sistine Chapel, and the absence of the sound of bells confirms that an agreement has not yet been reached. Until 1963, black smoke was also obtained by burning damp straw. In recent conclaves, however, the ballots have been moistened with chemical material. When the voting, however, reaches a positive outcome, only the ballots are burned, and the smoke is white. The color of the smoke serves to announce the outcome of the vote to the waiting faithful, as the official announcement takes place about an hour after the election.

Originally posted 2025-04-23 10:55:38.