Battle of Le Cateau –FRI 21 AUG 1914 – WED 26 AUG 1914

First actions of the BEF

The Kaiser, in an order of 19 August, referred to “General French’s insignificant little army”. The word “insignificant” was translated into English as “contemptible”. As a result of their outrageous insult, the 1914 BEF was dubbed the “Old Contemptibles.” Wilhelm II’s order demonstrated the German High Command’s contempt for the existence of the British Army on the Continent. Actually, Moltke welcomed the opportunity to foil the BEF as well as the French Army. This felt like a very real prospect given the chaos inside the Allies.

Lanrezac’s French Fifth Army pushed into Belgium with Sir John French’s BEF on its left. But as French Third and Fourth Armies fell back, the flank of Lanrezac’s Fifth Army was uncovered, and it found itself threatened by three German armies: from the east by Third Army (von Hausen); to the front by von Bülow’s Second Army; and von Kluck’s First Army to the west. In the Battle of the Sambre (21–23 August), the French met defeat.

Coordinating Operations with Allies and the First Battle of Mons for the British Expeditionary Force

However, the manoeuvres of the three German armies were poorly synchronized and they were unable to profit fully from their successes. On Lanrezac’s left, on 23 August the British fought their first battle in Western Europe since Waterloo, 99 years before. The difficulties Sir John French and Lanrezac faced in trying to coordinate their operations—neither of whom spoke the other’s language fluently—shows a lot about the difficulties associated with fighting alongside allies, and the British and French effectively engaged in two distinct but nearby battles.

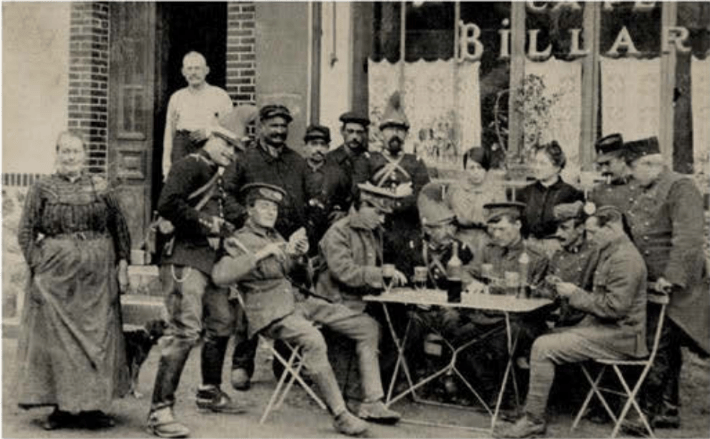

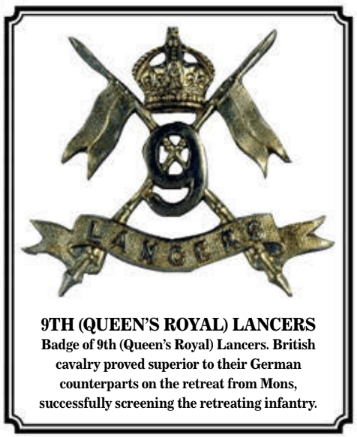

Mons was a classic encounter battle. Led by the 9th Lancers, the British II Corps under General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien reached Mons on 21–22 August. Mons was a mining town with chimneys and slag piles; hardly the best setting to engage in combat. By the next day, the 3rd and 5th Divisions were positioned in Mons, in the surrounding villages, and along the banks of the Mons-Condé canal. The Cavalry Division was held in reserve. They were caught off guard when the German First Army arrived because Kluck thought the BEF was at Tournai. Mounting clumsy frontal assaults, the attackers were bloodily repulsed in most places.

Challenges Facing the BEF During the Retreat from Mons

The outnumbered BEF was unable to maintain its position indefinitely due to the overwhelming pressure of the German soldiers and intense artillery bombardment. Mons was not an affair in which generals calmly manoeuvred troops as if on a giant chessboard. Rather, individual units and sub-units fought a series of almost private battles. The machine gun section of the 4th Royal Fusiliers conducted a rearguard action at a bridge that resulted in the award of two Victoria Crosses, one posthumous. Late on 23 August, II Corps began to fall back a new position.

Lanrezac’s Fifth Army was in full retreat. When the French learned of this, the BEF also withdrew and retreated from the Battle of Mons. Mons was a tactical victory for the British at the cost of 1,600 casualties (which was very light by later standards), but strategically the Germans had the upper hand and continued to drive forward. Command and control was fragile. General Sir Douglas Haig’s British I Corps managed to keep in touch with Lanrezac’s French Fifth Army, but he lost connection with Smith-Dorrien. Sir John French at General Headquarters (GHQ) was unable to exert much control over the two corps of the British Expeditionary Force.

The Retreat from Mons Continues, Culminating in the Battle of Le Cateau

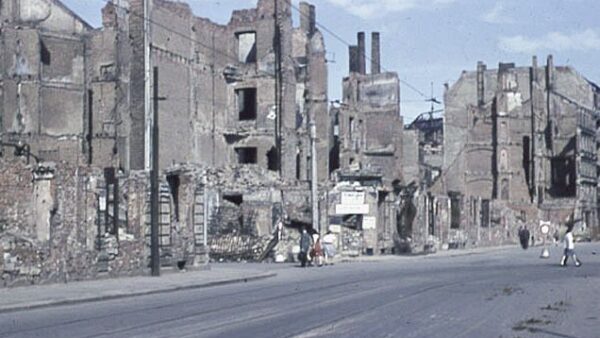

On 26 August, a German advance briefly threatened I Corps headquarters at Landrecies, causing some short-lived panic. For the BEF, the retreat from Mons was a gruelling experience. Apart from the hard march under a hot sun, retreating from an enemy they believed they had defeated was demoralizing for many British soldiers. Spirits rose when, on 26 August, the order was given to halt and deploy for battle. With the Germans in pursuit, Smith-Dorrien was forced to turn and fight at Le Cateau, 50km (30 miles) south of Mons. Once again, II Corps infl icted a sharp tactical defeat on the Germans, who were as tired as the British.

But this time British losses were much heavier – some 7,800. 1st Gordon Highlanders were accidentally left behind when the rest of the Corps retreated and were forced to surrender. The Germans, too, suffered badly and Smith-Dorrien was able to resume the retreat. The BEF was battered but intact and had fulfilled a vital role on the fl ank of French Fifth Army. French, however, temporarily lost his nerve and wanted to pull out of the line to refit. Kitchener had to cross over from England to forbid it. The end of August neared with the campaign still in the balance.