World War 1 MOBILIZATION –SAT 25 JUL 1914 –TUE 28 JUL 1914

The outbreak of war

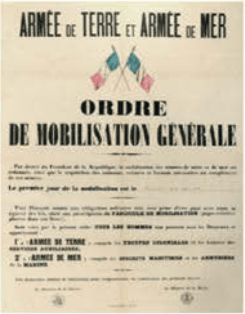

General staffs in Europe had been putting out complex mobilization plans for years before to 1914. In the eighteenth century, the majority of governments had embraced the practice of enlisting individuals for a predetermined, frequently brief amount of time before returning them to civilian life. Then, in an emergency, these reservists were called to the colors. This arrangement allowed armies to put vast numbers of men into the field. While the French had 73 divisions, 25 of which were made up of reserve personnel, the German field army had 82 infantry divisions and 31 reserve units.

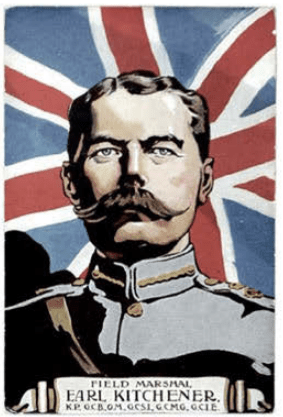

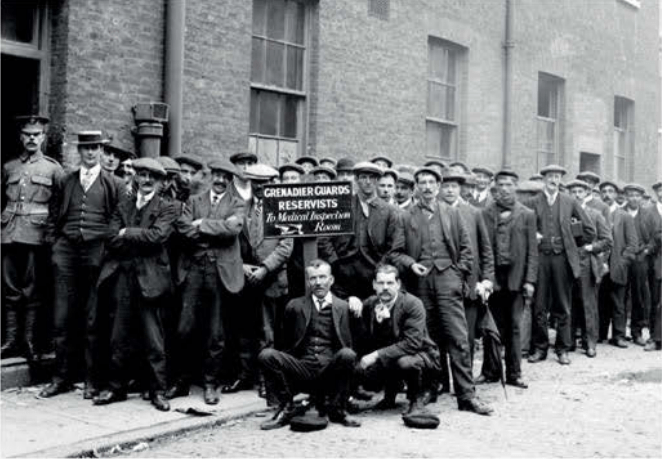

The major exception was Britain, which relied on a long-service regular army backed up by a volunteer part-time Territorial Force, rather than on conscription. Shortly after the war began, the new Secretary of State for War, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener called for mobilization of volunteers for a new, mass army. This ensured that by 1916 Britain had an army comparable in size to its allies and enemies. But in August 1914, Britain could only put a mere six infantry divisions in the field – in addition, of course, to the might of the Royal Navy.

Rival Mobilization Strategies: Germany’s Gamble and France’s Plan XVII

The war plans of the Great Powers dictated that no time could be wasted between mobilizing and fighting. The German pre-war plan, developed under General Alfred von Schlieffen, was designed to compensate for the fact that Germany would face a war on two fronts. Hurling the bulk of its forces westwards, and invading neutral Belgium to outflank the French frontier defences, Germany would defeat France in a matter of weeks. Its forces would then redeploy via the strategic railway system to face the Russian Army, which the Germans calculated would be slow to move. It was disregarded that encroaching on Belgian territory would probably involve the British in the conflict.

The operational concept was built around the idea of encirclement, a popular German military tactic that worked successfully for them in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 (and would be used repeatedly in the Second World War). If the French advanced into Lorraine, so much the better; the German trap would close behind them. The Schlieffen Plan, hotly debated by historians in recent years, stands as an example of a gamble of breathtaking proportions. Germany would be in serious danger if it collapsed.

French Army

The French army placed its faith in Plan XVII, a plan created by the French general staff under General Joseph Joffre’s direction. Plan XVII was founded on the concept of the all-out offensive, an aggressive military doctrine associated with Lieutenant General (later Marshal) Ferdinand Foch. Joffre and Foch both went on to have very important roles in the First World War. Major French forces would rush into Lorraine at the start of the war to retake the provinces that Germany had taken after the Franco-Prussian War, while others would go farther north.

Coordinated Allied Strategy on the Western Front

Everywhere, the French would carry the war to the enemy. As the consequence of secret talks between the British and French staffs, it was decided that the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), too small to carry out an independent strategy, would take its place on the left of the French Army, a decision reluctantly confirmed by an ad hoc war council of politicians and generals convened on the outbreak of war. The Belgian Army, less than 120,000 strong in 1914, could do little but resist the Germans mobilization as best they could until joined by Franco-British forces.

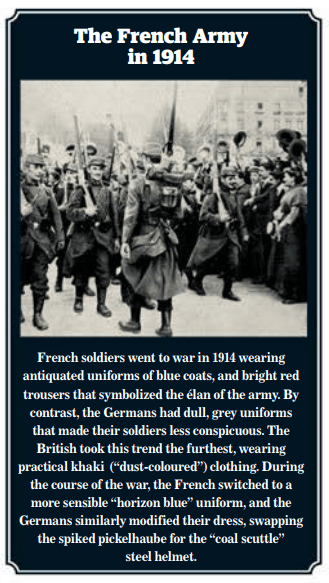

The French, British and German armies were armed with broadly similar weapons – bolt-action, magazine rifl es capable of rapid fire; modern, quick-fi ring artillery; and a limited number of machine guns. All of them still had a sizeable cavalry force that was equipped with both swords and fi rearms for the charge and for scouting. Every army also possessed a small number of undeveloped aircraft.

Early War Offensive Doctrines and their Tragic Consequences

General staffs had studied the most recent military campaigns, in South Africa (1899–1902) and Manchuria (1904–05), and had incorporated the perceived lessons into their thinking. None were unaware of the devastating power of modern weapons, or the diffi culty in overcoming fi xed fortifi cations. To strike fi rst and win quickly, before the front could congeal into trench warfare, seemed a logical extrapolation from recent wars; and the Russo-Japanese War apparently demonstrated that determined troops with high morale could overcome entrenched defenders, albeit at a heavy cost in casualties.

The French were the most extreme exponents of the cult of the offensive and the “moral battlefi eld”, in which heavy emphasis was placed on morale (the words being used interchangeably at this time), but these concepts also infl uenced the British and Germans. These pre-war doctrines were not entirely wrong, but undoubtedly contributed to the huge “butcher’s bill” in the early months of the war…

Originally posted 2023-10-12 13:24:30.

There is 1 comment