Schlieffen Plan-WED 29 JUL 1914 –SAT 22 AUG 1914

Lorraine and the Schlieffen Plan

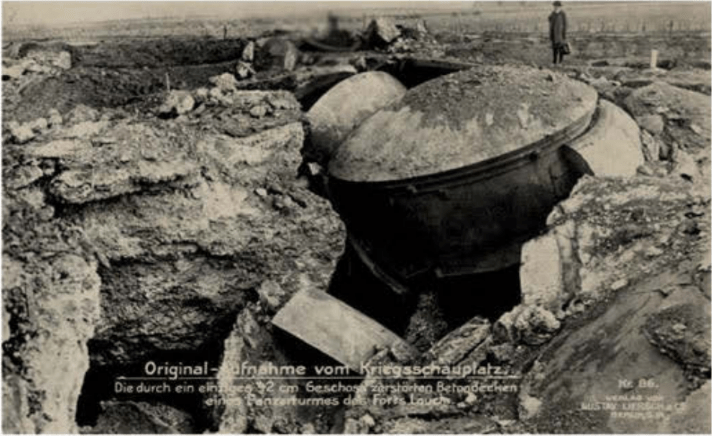

The first shots of the war were fired by the Austrians against the Serbs on 29 July, but the outbreak of fighting in Western Europe was not long delayed. The first major clash came on 5 August with the German attack on the Belgian fortress of Liège, which held out until 13 August. This was crucial because the longer the Belgians were able to stop the German assault, the longer the Schlieffen Plan would be delayed.

Before withdrawing into the citadel of Antwerp on August 20 and losing the Belgian city of Brussels the same day, the Belgian Army maintained the line of the River Gette. The Germans kept pushing forward, taking the Meuse River citadel of Huy, and starting a brief siege of Namur, which was eventually defeated on August 23.

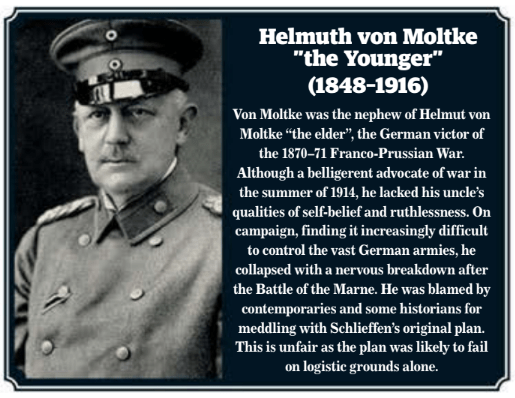

Moltke, who had succeeded Schlieffen as Chief of the Great General Staff in 1906, was forced to deploy a sizeable force to mask Antwerp, and to protect the fl ank of the main German advance from a Belgian sortie. In an exhibition of British maritime strength, a British force reinforced the port on October 5. This further weakened and slowed the German main effort. Partly out of frustration, partly to discourage guerrilla activity, the Germans carried out Schrecklichkeit, a policy of terror that included sacking the medieval city of Louvain and killing civilians.

Early Implementations of Offensive Doctrines and Setbacks on Both Sides

Although usually overstated, the oft-mocked Allied propaganda on German atrocities was based in reality. On August 6, a French corps was sent into Alsace as part of Plan XVII, but the defenders turned it back. The town of Mulhouse was taken on August 8 as a consequence of a further assault led by General Paul Pau. The French troops were greeted by cheering crowds, glad to welcome their liberators. However, shortly afterwards the victorious French were ordered to abandon their gains so that troops could be switched to meet the growing crisis to the north.

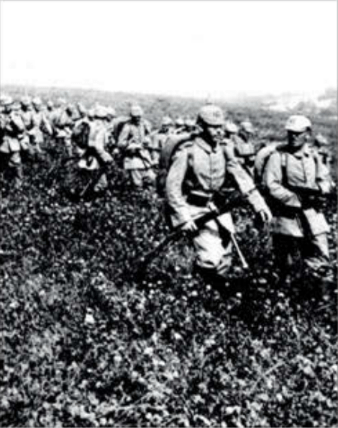

The major French offensive into Lorraine commenced on 14 August with two Armies (First and Second). This was a complex undertaking, as the further the French advanced, the wider their frontage of attack became. In spite of the fact that, according to the Schlieffen Plan, the German forces should have kept to the defensive, they went onto the attack and on 20 August defeated the French in the twin battles of Morhange and Sarrebourg, and then pushed on to the French frontier. Some French formations fought well.

Failures and Heavy Losses on Both Sides as Offensive Doctrines Break Down

General Foch’s XX (“Iron”) Corps held its ground stubbornly at Morhange, and was preparing to counter-attack, when to Foch’s astonishment it received orders to pull back. His Chief of Staff, General Denis Duchêne, made a nasty remark, “You don’t know what is happening to the neighboring corps.” Weary but in good order, XX Corps protected the Second Army’s retreat.

A few days later, a subordinate officer of the 131st Infantry Regiment who was serving with Foch’s son was killed in action nearby. The French stabilized the situation, just as a new German offensive was getting underway. Joffre, the Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) had ordered two armies to attack into the hilly, wooded terrain of the Ardennes in the belief that the German forces in this sector were weak.

This misapprehension was based on an intelligence failure: the French had not realized the extent to which the Germans would use reserve troops to create new divisions. On August 21 and 22, the invaders were engaged in encounter fights (unexpected meeting engagements) at Neufchâteau and Virton, where they sustained additional serious losses and were forced to retreat beyond the River Meuse.

Plan XVII was proving a bloody failure. Around 300,000 French soldiers became casualties in the Battle of the Frontiers. The soldiers, infantry, and artillery have been put to a great deal of strain, according to a dispatch from the Second Army in Lorraine. Our artillery is held at a distance by the long-range artillery of our enemy; it cannot get close enough for counterbattery fire.

Joffre’s leadership amid setbacks and transition to the fighting in Belgium

Our infantry has attacked with élan, but have been halted primarily by enemy artillery fire and by unseen enemy infantry hidden in trenches.” Despite the failures, “Papa” Joffre maintained his composure under pressure and zealously fired any commanders who were either ineffective or just unfortunate. He demoted skilled, battle-tested commanders from lower in the military’s echelons in less than a month, removing 50 generals, including no less than 38 divisional commanders. One such officer was Ferdinand Foch, promoted to command Ninth Army. By mid-August, both Joffre and Moltke were less focused on Alsace-Lorraine. Now they looked towards Belgium. For it was there, as the Germans advanced, a major crisis was brewing.

Schlieffen Plan–Wikipdia

Originally posted 2023-10-13 10:36:40.

There is 1 comment